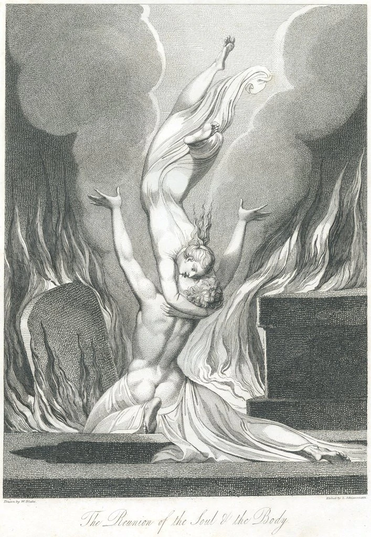

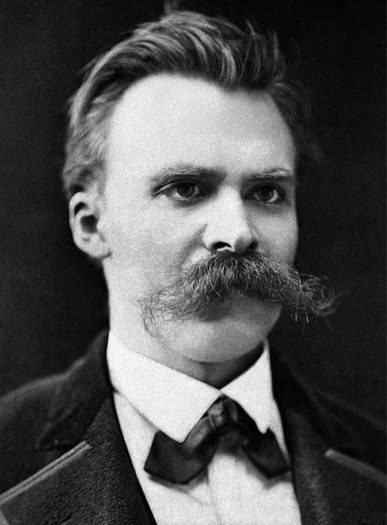

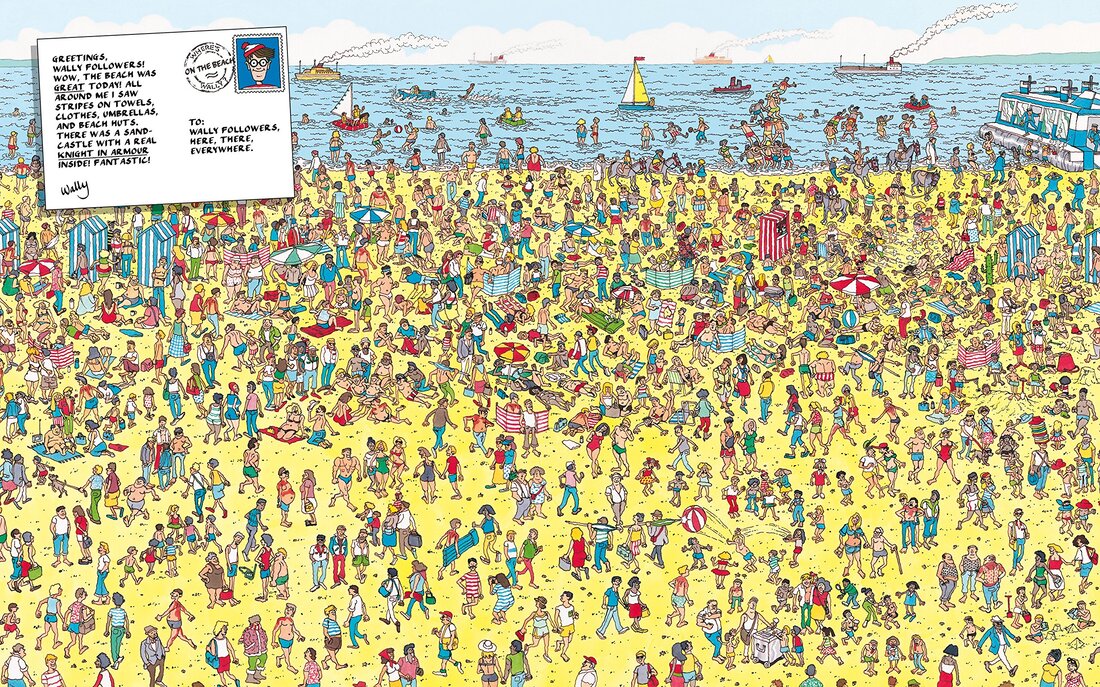

Serious Play with Evolutionary Ideas Have I mentioned already that I am part of an arts & science collective here in Vienna? It's called THE ZONE. Yes, you're right. I actually did mention it before. What is it about? And what, in general, is the point of arts & science collaborations? This post is the start of an attempt to give some answers to these questions. It is based on a talk I gave on Mar 12, 2022 at "Hope Recycling Station" in Prague as part of an arts & science event organized by the "Transparent Eyeball" collective (Adam Vačkář and Jindřich Brejcha). I'll start with this beautiful etching by polymath poet William Blake, from 1813. It's called "The Reunion of the Soul and the Body," and shows a couple in a wild and ecstatic embrace. I suppose the male figure on the ground represents the body, while the female soul descends from the heavens for a passionate kiss amidst the world (a graveyard with an open grave in the foreground, as far as I can tell) going up in smoke and flames. This image, rich in gnostic symbolism, stands for a way out of the profound crisis of meaning we are experiencing today. Blake's picture graces the cover of one of the weirdest and most psychoactive pieces of literature that I have ever read. In fact, I keep on rereading it. It is William Irwin Thompson's "The Time Falling Bodies Take to Light." This book is a wide-ranging ramble about mythmaking, sex, and the origin of human culture. It sometimes veers a bit too far into esoteric and gnostic realms for my taste. But then, it is also a superabundant source of wonderfully crazy ideas and stunning metaphorical narratives that are profoundly helpful if you're trying to viscerally grasp the human condition, especially the current pickle we're in. It's amazing how much this book, written in the late 1970s, fits the zeitgeist of 2022. It is more timely and important than ever. THREE ORDERS So why is Blake's image on the cover? "Myth is the history of the soul" writes Thompson in his Prologue. What on Earth does that mean? Remember, this is not a religious text but a treatise on mythmaking and its role in culture. (I won't talk about sex in this post, sorry.) Thompson suggests that our world is in flames because we have lost our souls. This is why we can no longer make sense of the world. A new reunion of soul and body is urgently needed. Thompson's soul is no supernatural immortal essence. Instead, the loss of soul represents the loss of narrative order, which is the story you tell of your personal experience and how it fits into a larger meta-narrative about the world. A personal mythos, if you want. We used to have such a mythos but, today, we are no longer able to tell this story of ourselves in a way that gives us a stable and intuitive grip on reality. According to cognitive psychologist John Vervaeke, the narrative order is only one of three orders which we need to get a grip, to make sense of the world. It is the story about ourselves, told in the first person (as an individual or a community). The second-person perspective is called the normative order, our ethics, our ways of co-developing our societies. And the third-person perspective is the nomological order, our science, the rules that describe the structure of the world, which constrains our agency and guides our relationship with reality (our agent-arena relationship). All three orders are in crisis right now. Science is being challenged from all sides in our post-truth world. Moral cohesion is breaking down. But the worst afflicted is the narrative order. We have no story to tell about ourselves anymore. This problem is at the root of all our crises. That is exactly what Thompson means by the soullessness of our time. THE OLD MYTHOS... But what is the narrative order, the mythos, that was lost? As I explain in detail elsewhere, it is the parable (sometimes wrongly called allegory) of Plato's Cave. We are all prisoners in this cave, chained to the wall, with an opening behind our backs that we can't see. Through this opening, light seeps into the cave, casting diffuse shadows of shapes that pass in front of the opening onto the wall opposite us. These shadows are all we can see. They represent the totality of our experiences. In Plato's tale, a philosopher is a prisoner who escapes her shackles to ascend to the world outside the cave. She can now see the real world, beyond appearances, in its true light. For Plato, this world consists of abstract ideal forms, to be understood as the fundamental organizational principles behind appearances. He provides us with a two-world mythology that explains the imperfection of our world, and also our journey towards deeper meaning. This journey is a transformative one. It is central to Plato's parable. He calls it anagoge (ancient Greek for "climb" or "ascent"). The philosopher escaping the cave must become a different person before she can truly see the real world of ideal forms. Without this transformation, she would be blinded by the bright daylight outside the cave. Anagoge involves a complexification of her views and a decentering of her stance, away from egocentric motivations to an omnicentric worldview that encompasses the whole of reality. When she returns to the cave, she is a completely different person. In fact, the other prisoners, her former friends and companions, no longer understand what she is saying, since they have not undergone the same transformations she has. The only way she can make them understand is to convince them to embark on their own journeys. However, most of the prisoners do not want to leave the cave. They are quite comfortable in its warm womb-like enclosure. With his parable, Plato wanted to destroy more ancient mythologies of gods and heroes. Ironically, in doing so, he created an even more powerful myth that governed human meaning-making for almost two-and-a-half millennia. After his death, it was taken up by the Neoplatonists and then by St. Augustine. It entered the mythos of Christianity as the spiritual domain of God, which lies beyond the physical world of our experience. Only faith, not reason, can grant you access. Later, this idea of a transcendent realm was secularized by Immanuel Kant. who postulated a two-world ontology of phenomena and noumena, the latter ("das Ding an sich") completely out of reach for a limited human knower. ... AND ITS DOWNFALL All of this was brutally shattered by Friedrich Nietzsche (although others, such as Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel and Auguste Comte, also contributed enthusiastically to the demolition effort). Nietzsche is the prophet of the meaning crisis. "God is dead, and we have killed him" doesn't leave much room anymore for the spiritual realm of traditional Christianity. What Nietzsche means here is not an atheistic call to arms. It is the observation that traditional religion already has become increasingly irrelevant for a growing number of people, and that this process is inevitable and irreversible in our modern times. Nietzsche also destroys Kant's transcendental noumenal domain, all in just one page of "The Twilight of the Idols," which is unambiguously entitled "History of an Error." When Nietzsche is through with it, two-world mythology is nothing more than a heap of smoking rubble. And things have gotten only worse since then. As Nietzsche predicted, the demolition of the Platonic mythos was followed by an unprecedented wave of cynical nihilism over what we could call the long 20th century, culminating in the postmodern relativism of our post-fact world. Under these circumstances, any attempt at reconstructing the cave would be a fool's hope. A NEW MYTHOS? But we can try to do better than that! What Thompson and Vervaeke want, instead of crawling back into the womb of the cave, is a new mythos, a new history of the soul, (meta-)narratives adequate for the zeitgeist of the 21st century. But who would be our contemporary mythmakers? Thompson points out a few problems in "Falling Bodies:" "The history of the soul is obliterated, the universe is shut out, and on the walls of Plato's cave the experts in the casting of shadows tell the story of Man's rise from ignorance to science through the power of technology." In Thompson's view, scientists are the experts in the casting of shadows, generating ever more sophisticated but shallow appearances, without ever getting to the deep underlying issues. What about artists then? "In the classical era the person who saw history in the light of myth was the prophet, an Isaiah or Jeremiah; in the modern era the person who saw history in the light of myth was the artist, a Blake or a Yeats. But now in our postmodern era the artists have become a degenerate priesthood; they have become not spirits of liberation, but the interior decorators of Plato's cave. We cannot look to them for revolutionary deliverance." Harsh: postmodern artists as the interior decorators of Plato's cave. Shiny surface and distanced irony over deep meaning and radical sincerity. The meaning crisis seems to have fully engulfed both the arts and the sciences. Thompson's pessimistic conclusion is that, in their current state, neither are likely to help us restore the narrative order. WISSENSKUNST This is where Thompson (pictured above) proposes the new practice of wissenskunst. Neither science nor art, yet also a bit of both (in a way). He starts out with a reflection on what a modern-day prophet would be: "The revisioning of history is ... also an act of prophecy―not prophecy in the sense of making predictions, for the universe is too free and open-ended for the manipulations of a religious egotism―but prophecy in the sense of seeing history in the light of myth." Since artists are interior decorators now, and scientists cast ever more intricate shadows in the cave, we need new prophets. But not religious ones. More something like: "If history becomes the medium of our imprisonment, then history must become the medium of our liberation; (to rise, we must push against the ground to which we have fallen). For this radical task, the boundaries of both art and science must be redrawn. Wissenschaft must become Wissenkunst." (Wissenskunst, actually. Correct inflections are important in German!) The task is to rewrite our historical narrative in term of new myths. To create a new narrative order. A story about ourselves. But what does "myth" mean, exactly? In an age of chaos, like ours, myth is often taken to be "a false statement, an opinion popularly held, but one known by scientists and other experts to be incorrect." This is not what Thompson is talking about. Vervaeke captures his sense of myth much better: "Myths are ways in which we express and by which we try to come into right relationship to patterns that are relevant to us either because they are perennial or because they are pressing." So what would a modern myth look like? ZOMBIES! Well, according to Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, there is only one modern myth: zombies! Vervaeke and co-authors tie the zombie apocalypse to our current meaning crisis: zombies are "the fictionally distorted, self-reflected image of modern humanity... zombies are us." The undead live in a meaningless world. They live in herds but never communicate. They are unapproachable, ugly, unlovable. They are homeless, aimlessly wandering, neither dead nor alive. Neither here nor there. They literally destroy meaning by eating brains. In all these ways, zombification reflects our loss of narrative order. Unfortunately, the zombie apocalypse is not a good myth. It only expresses our present predicament, but does not help us understand, solve, or escape it. A successful myth, according to Vervaeke, must "give people advice on how to get into right relationship to perennial or pressing problems." Zombies just don't do that. Zombie movies don't have happy endings (with only one exception that I know of). The loss of meaning they convey is rampant and terminal. Compare this with Plato's myth of the cave, which provides us with a clear set of instruction on how to escape our imperfect world of illusions. Anagoge frees us from our shackles. What's more, it is achievable using only our own faculties of reason. No other tools required. In contrast, you can only run and hide from the undead. There is no escaping them. They are everywhere around you. The zombie-apocalypse is claustrophobic and anxiety-inducing. It leaves us without hope. We need better myths for meaning-making. But how to create them? Philip Ball, in his excellent book about modern myths, points out that you cannot write a modern myth on purpose. Myths arise in a historically contingent manner. In fact, they have no single author. Once a story becomes myth, it mutates and evolves through countless retelling. It is the whole genealogy of stories that comprises the myth. Thompson comes to a very similar conclusion when looking at the Jewish midrashim, for example, which are folkloristic exegeses of the biblical canon. For it to be effective, a myth must become a process that inspires. Just look at the evolution of Plato's two-world mythology from the original to its neoplatonist, Christian, and Kantian successors. So where to begin if we are out to generate a new mythology for modern times? I think there is no other way than to look directly at the processes that drive our ability to make sense of the world. If we see these processes more clearly, we can play with them, spinning off narratives that might, eventually, become the roots of new myths, myths based on cognitive science rather than religious or philosophical parables. THE PROBLEM OF RELEVANCE By now, it should come as no surprise that rationality alone is not sufficent for meaning-making. We have talked about the transformative process of anagoge, in which we need to complexify and decenter our views in order to make sense of the world. What is driving this process? The most basic problem we need to tackle when trying to understand anything is the problem of relevance: how do we decide what is worth understanding in the first place? And once we've settled on some particular aspect of reality, how do we frame the problem so it actually can be understood? A modern mythology must address these fundamental questions. Vervaeke and colleagues call the process involved in identifying relevant features relevance realization. At the danger of simplifying a bit, you can think of it as a kind of "where is Wally" (or "Waldo" for our friends from the U.S.). Reality bombards us with a gazillion of sensory impressions. Take the crowd of people on the beach in the picture above. How do we pick out the relevant one? Where is Wally? We cannot simply reason our way through our search (although some search strategies will, of course, be more reasonable than others). We do not yet have a good understanding of how relevance realization actually works, or what its cognitive basis is, but there are a few aspects of this fundamental process that we know about and that are relevant here. On the one hand, we must realize that relevance realization reaches into the depth of our experience, arising at the very first moments of our existence. A newborn baby (and, indeed, pretty much any living organism) can realize what is relevant to it. We must therefore conclude that this process occurs at a level below that of propositional knowledge. We can pick out what is relevant before we can think logically. On the other hand, relevance realization also encompasses the highest levels of cognition. In fact, we can consider consciousness itself as some kind of higher-order recursive relevance realization. Importantly, relevance realization cannot be captured by an algorithm. The number of potentially relevant aspects of reality is indefinite (and potentially infinite), and cannot be captured in a well-formulated mathematical set, which would be necessary to define an algorithm. What's more, the category of "what we find relevant" does not have any essential properties. What is relevant radically depends on context. In this regard, relevance is a bit like the concept of "adaptation" in evolution. What is adaptive will radically depend on the environmental context. There is no essential property of "that which is adaptive." Similarly, we must constantly adapt to pick out the relevant features of new situations. Thus, in a very broad but also deep sense, relevance realization resembles an evolutionary adaptive process. And just like there is competition between lots of different organisms in evolution, there is a kind of opponent processing going on in relevance realization: different cognitive processes and strategies compete with each other for dominance at each moment. This explains why we can shift attention very quickly and flexibly when required (and sometimes when it isn't), but also why our sense-making is hardly consistent across all situations. This is not a bad thing. Quite the opposite, it allows us to be flexible while maintaining an overall grip on reality. As Groucho Marx is supposed to have said: "I have principles, but if you don't like them, I have others." INVERSE ANAGOGE & SERIOUS PLAY Burdened with all this insight into relevance realization, we can now come up with a revised notion of anagoge, which is appropriate for our secular modern times. It is quite the inverse of Plato's climb into the world of ideals. Anagoge now becomes a transformative journey inside ourselves and into our relationship with the world. A descent instead of an ascent. Transformative learning is a realignment of our relevance realization processes to get a better grip on our situation. We can train this process through practice, but we cannot step outside it to observe and understand it "objectively." We cannot make sense of it, since we make sense through it. Basically, the only way to train our grip on reality is to tackle it through practice, more specifically, to engage in serious play with our processes of relevance realization. To quote metamodern political philosopher Hanzi Freinacht, we must "... assume a genuinely playful stance towards life and existence, a playfulness that demands of us the gravest seriousness, given the ever-present potentials for unimaginable suffering and bliss." Serious playfulness, sincere irony, and informed naivité. This is what it takes to become a metamodern mythmaker. So this is the beginning of our journey. A journey that will eventually yield a new narrative order. Or so we hope. It is not up to us to decide, as we enter THE ZONE between arts and science. Our quest is ambitious, impossible, maybe. But try we must, or the world is lost. This post is based on a lecture held on March 12, 2022 at the "Transparent Eyeball" arts & science event in Prague, which was organized by Adam Vačkář and Jindřich Brejcha. Based on work by William Irwin Thompson, John Vervaeke, and Hanzi Freinacht.

1 Comment

Zumitbewohner

22/7/2022 09:36:06

Very interesting article! I was wondering - isn't this a very narrow idea of mythology? A structuralist like Roland Barthes would say that a lot of the ways in which we perceive the world and make judgements about it is dominated by mythology - the cultural zeitgeist of an era. Some very obvious examples would be - thinking of every problem as a potential for profit by making a product, or thinking of the brain as a computer or whatever machine is popular in an era. There might be several not-so-obvious 'structures' which restrict our thought and canalize how we arrive at conclusions. Is it so easy - or rather possible at all, to get out of the cave in such a definition of mythology? Are the nomological and normative order so different from a narrative order then?

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Johannes Jäger

Life beyond dogma! Archives

May 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed