|

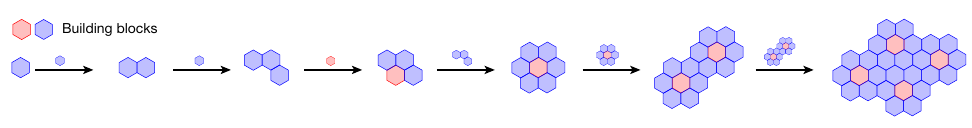

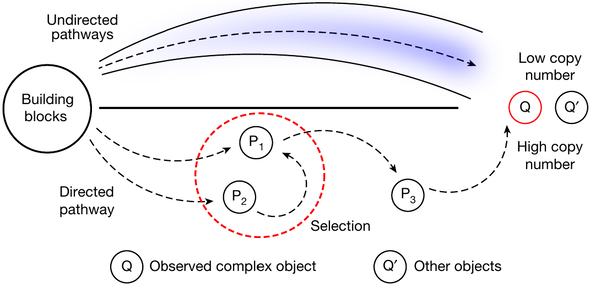

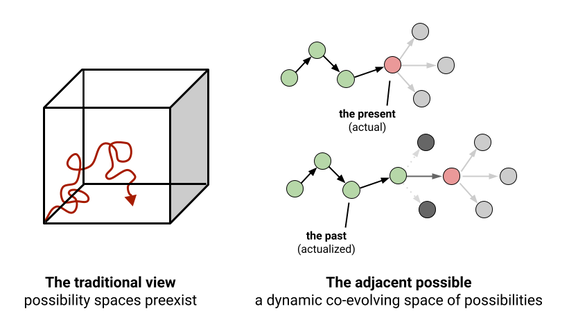

Drawings by Marcus Neustetter. A graveyard of zombie concepts. I’ve done it. I’ve read the entire 43 pages of Mike Levin’s “Technology Approach to Mind Everywhere” (TAME) paper. Carefully. Yes, you may pity me. Indeed, I like to suffer. But I also like my suffering to be productive. So I’ve decided to write up a philosophical take-down of the massive theoretical thingamajig that is TAME. It’s the ultimate conceptual chimera, packed with plenty of intriguing ideas that are cobbled together in the cubist manner of Levin’s own Picasso creatures. Unfortunately, all of it is built on a metaphysical foundation that amounts to nothing but hot air. A big philosophical smokescreen. I’ve written about it before. Twice, in fact. But never systematically and in depth, like I intend to do here. Don’t worry: this is going to be a philosophical argument, not some kind of personal vendetta. Yet, to understand the nature of Levin’s approach, you need to know two things about the man and the behavioral patterns he exhibits. First, he is a prototypical product of our current society and research system, a high-stakes gambler for social capital and reputation. To understand the structure of his thinking, you need to understand the main motivation behind his staggeringly prodigious output: it is not primarily the search for truth, but the maximization of impact that drives him. He is a man on a mission. Levin’s main guiding principle is to be the proponent of ideas that are not only workable and world-changing, but also popular among the right kind of target audience. The two go together, hand in hand, as you will see. Second, he is beloved by the tech affine. Levin’s primary target audience are those who crave to believe in our upcoming techno-utopian salvation. In a recent article for Noema Magazine, he has explicitly come out as a proponent of transhumanism, stating that the best possible long-term outcome for humanity (our kids!) would be to supplant ourselves with “creative agents with compassion and meaningful lives that transcend [our] limitations in every way.” Not subtle. And more than just a little bit eugenicist. I don’t know about you, but I find this kind of ideology creepy. And delusional as well. Given this context, let’s dive right into the philosophical gist of the argument. What is TAME? Well. TAME is many things. Whatever you would like it to be, really. The chimera is also a chameleon. THE "I AIN'T GOT NO PHILOSOPHY" PHILOSOPHY First and foremost, TAME proclaims itself to be a radical form of empiricism. It eschews unnecessary philosophical speculation. It presents itself as hard-nosed, rigorously scientific — putting forward lots of experimentally testable predictions. And most important of all: it purports to focus strictly on “third-person observable” properties. Funnily enough, every single one of these fundamental observations are loaded with metaphysical assumptions. So let’s take a little tour. TAME’s first underlying observation goes like this: there is no clear distinction between entities in the world that have mind, and those that do not. No “bright line” to be drawn between it knows and it “knows,” as Levin puts it. We can’t tell the difference. He calls this gradualism, like the evolutionary gradualism of Darwin. It doesn’t take much to notice that the man has a way with words. And a knack for grandiose associations. Levin’s concept of a mind is intimately tied to his notion of a self. Such a self is defined by agency, which is the ability to pursue goals. Selves must also have memories (to remember who they are, presumably, and to allow for learning). And the self is the locus for credit assignment. The self is what is responsible for its actions, an autonomous source of causal influence. If all this seems a little bit esoteric to you, don’t fret. Levin assures us it’s all pretty down to earth, as long as you consider that “nothing in biology makes sense, except in the light of teleonomy.” Teleonomy is what we call the apparent goal-directedness (or teleology) you can observe in the behavior of living systems. Below the surface level of appearances, or so the doctrine goes, it is based on a kind of automated genetic or developmental program which determines growth and behavior of a self. It is this program that gets shaped and adapted by natural selection during evolution. The self’s goals are defined in terms of feedback regulation, rooted in the concept of homeostasis, and the science of cybernetics. Echoing philosopher Dan McShea, Levin likens a self to some kind of thermostat. Goal-directed behavior is nothing but “upper-directedness:” living systems learn how to optimize their path toward some target state (set, somewhat mysteriously, from a higher level of organization) by minimizing the energy they have to expend to get there. It’s all perfectly mechanistic and scientific, you see. Well. I’m not so sure about that. For one, it is not quite clear how the self chooses a target to pursue in the first place. But let’s put this issue aside for the moment. What’s important here is that “goal-directed” “agency” can occur in any kind of system, living or nonliving. In fact, Levin claims that it pervades all of physics, as the principle of least action in classical physics and relativity, for example, or the principle of free-energy minimization in living and other far-from-equilibrium systems. Some people claim that Levin is the savior that will deliver us from reductionism in biology. But it is evident from what I just said that he does his very best to ground his framework in staunchly mechanistic and reductionist conceptions of words like “self,” “agent,” and “goal.” They describe teleonomical appearances that are ultimately governed by evolved deterministic programs. This is a version of what philosopher Dan Dennett called the intentional stance: we talk about selves as if they were pursuing their own goals, as if they had agency, but it’s all just simple mechanics underneath. In sum: Levin’s terms suggest something very different than what they actually represent. You will see that this is a pervasive feature of everything he does or says. Bait-and-switch, is what it’s called. The axis of persuadability. WHERE IS MY MIND? TAME’s second basic observation is that selves have no privileged material substrate. Levin calls this “mind-as-can-be.” And also: what defines something as a self does not depend on that self’s evolutionary origin or history. (Wait, what!?) Yes: anything can be a self! TAME, as a philosophy, is a form of panpsychism. Levin explicitly states this, here and also elsewhere. He talks about living and nonliving “intelligences” that can manifest in societies, swarms, colonies, organisms (from humans to bacteria), but also in weather patterns, or rocks. Yes, rocks. Levin believes rocks are in some minimal way intelligent. And also: fundamental particles. You find this hard to believe? Bear with us. Levin can explain everything. He’s good at that, actually. The presentation is always crystal clear and easily accessible. Not just his writing style, but also the elaborate design of the figures stand out. Kudos for that. I mean it. Shame it’s not put to better use… Here’s the basic idea: every particle in the universe has some kind of proto-intelligence (and not even less so than a rock). What Levin means by this is that such particles follow “teleological” principles (e.g., the principle of least action, as mentioned above). And also: they exhibit what he calls “persuadability.” Persuadability is probably his most unfamiliar and counterintuitive concept, so it’s worth examining it in a bit more detail: it represents the degree to which one can come up with tools to “rationally modify” an entity’s behavior. This is tightly connected to Levin’s simplistic concept of “intelligence.” Both are grounded in a philosophy called pancomputationalism. I criticize this worldview at length in my book. Be that as it may, Levin is a died-in-the-wool panpsychist pancomputationalist. I know, it does not exactly flow off the tongue. And panpsychism and pancomputationalism are often seen as diametrically opposed. Yet, the extremes of this spectrum do touch, bending the axis around to form a circle which closes at the point where Levin’s approach is located. You can have your cake and eat it! He, like many fellow (pan)computationalists, simply equates “intelligence” with problem-solving capacity — nothing more, nothing less. Intelligence is the ability to explore a well-defined search space. And that’s that. The more persuadable a self is (the more it can be coaxed to exhibit different behaviors), the larger the search space it can explore and the more flexible its ways of moving around within this space of possibilities. This is why Levin thinks the weather is intelligent to some degree: we can make it behave in many different ways. In principle, at least. We’re certainly not very good at it yet in practice. So, there is an “axis of persuadability,” according to Levin. On one end, particles and rocks are not very persuadable. On the other end, people are very much so! That’s why we are more intelligent than a rock. Now that, at least, is good news! Levin has a clever way to show just how much more intelligent we are: he uses what he calls cognitive cones to classify different intelligences according to their sophistication. These cones, inspired by relativity diagrams in physics, show how far the concern of a self extends in space and time, both into the future and into the past. A tall cone means you’re in it for the long run. A wide cone means you’re concerned about many things that are happening around you in the present. What remains to be explained, however, is how we got to be so much smarter than rocks. Levin’s surprisingly simple answer to this is collectivity: every higher self is a collective intelligence and, therefore, also a collective self. We are literally legions. Higher-level agents are made of lower-level ones and so on. And just like a parallel computer can solve problems more efficiently, you become more intelligent by scaling up and binding together several individual intelligences. This is the basis of Levin’s gradualism: the more intelligences in a collective, the more intelligent the resulting higher-level self. Simple. What results from all this are a plethora of diverse intelligences: selves that exist at multiple scales, are made of various material substrates, take various forms, and manifest in various behaviors, with the one common denominator that they all solve problems. And because there is intelligence everywhere, it is okay to say that there is cognition, and even some form of consciousness in every self that is persuadable. What a powerful vision! A mindful panpsychist world, alive and filled with conscious experience everywhere. Or so it seems. In reality, it’s all based on universal computation underneath. And in truth, it is nothing but a shiny package for a rather sinister ideology. We’ll get to that in due time. Bioelectricity is everything! THE BODY ELECTRIC There’s a lot more in this monumental paper. Go check it out for yourself! It’s a true treasure trove. As I said, the whole framework is packed with ideas, and many of them are not uninteresting, I admit. But instead of going into more detail, I’d like to illustrate the core concepts introduced above with some concrete examples. Levin himself dedicates a good part of the paper to a particular case study: TAME applied to morphogenesis in organisms — the kind of growth processes that shape the organism’s form. Or “somatic cognition,” as he likes to call it. This case study reveals just how weird Levin’s view really is. He sees organismic development (or ontogenesis, as I’d call it) as a fundamentally teleological process, oriented towards the final goal of attaining the organism’s adult form. As evidence for this controversial view, he uses regenerative processes in flatworms and frogs, which can regrow amputated heads and legs, respectively. The pathways by which such regeneration is achieved are very different from those of normal ontogenesis. And many pathways mapped to one single outcome implies teleology, to Levin at least. (To me, it implies the presence of an attractor, nothing more… but never mind: Levin would also see that as some form of teleology.) If your conceptual feathers are ruffled already, just wait for what’s coming next: Levin claims the goal-orientedness of morphogenesis means it must be cognitive in nature. His reasoning goes as follows, as already mentioned above: cognition is what underlies intelligence which, in turn, is what allows you to optimize the path towards your goal. Thus ontogenesis is cognitive and intelligent, because it optimizes the organism’s path towards its goal, that is, its adult form. Are you still with me? I’m not sure I am. What do we gain, you may rightfully ask, from treating morphogenesis as the expression of an intelligent goal-oriented self? It sounds a little crazy. But some of the implications are actually quite down to earth: one conclusion, for instance, is that a higher-level “intelligence” like morphogenesis in multicellular organisms must be a collective phenomenon. It is happening across many levels of organization. Fair enough, and very likely true! This, by the way, is why Levin is widely seen as an anti-reductionist messiah of some kind: he correctly and prominently makes the point that ontogenesis cannot simply be reduced to the genetic level. Instead, he proposes, the intelligence of morphogenesis is coordinated through bioelectric fields. This may or may not have something to do with the fact that he has established his career as an experimental researcher working on such fields. When you have a hammer, everything looks like a nail. And Levin is the master hammerer. Of course, he has evidence that bioelectricity is of fundamental importance: it does not only occur in our nervous system, in the form of signals transmitted between neurons, but the same action potentials that are found in nerve cells can also be detected in other somatic tissues, and even in plants, amoeba, and bacteria. Voilà! Here we have our basal cognition: bioelectric fields established in non-neural tissues. Admittedly, these fields are much simpler and operate at much slower rates than the electric signaling networks in our brains. Less persuadability, perhaps, but not unintelligent either! They achieve what Levin calls morphological coordination. In particular, Levin is fascinated with cells that undergo “mind meld.” Yes, he uses this as a technical term. Cells in many tissues interconnect their cytoplasm directly via organelles that are called gap junctions. And gap junctions are everywhere, once you start looking. Now, here’s the thing: Levin’s experimental work on bioelectric fields is actually quite interesting, and I have no immediate reason to doubt that it is technically and methodologically sound. It is certainly original. It would really stand on its own merit, you’d think. But, apparently, this is not enough for Levin. He needs a fancy wrapper to boost his megalomaniac message. Hence the talk about “intelligent development” and Levin’s rather outsized claims, often promulgated through press releases, podcasts, and online videos, rather than his numerous peer-reviewed publications: bioelectricity is elevated from an interesting mechanism among many, to the substrate of all ontogenetic selves. Nay, a unifying principle for all of biology! Genes go home! Also: forget about tissue biophysics. Bioelectricity cures cancer, it means cells can think, and motile cell cultures become “biobots” built from “agential materials,” a new kind of “synthetic machine.” The hyperbole knows no limits: we now can engineer life, the weather, and, ultimately, the fundamental particles of the universe too! A brave new world awaits, with us as masters of our own destiny. Who would not want to buy into a narrative like this? Well. I don’t want to. I’ll tell you why in a minute. But before I get to that, let me dismantle the whole cobbled-together intellectual contraption that Levin has constructed. This is one of the six impossible things I can accomplish before breakfast. Let’s go! THE EMPEROR HAS NO CLOTHES So what is wrong with TAME? At first sight, it seems to hold together pretty well, don’t you think? Maybe in a slightly eccentric way, with all its talk about intelligences and engineering. But eccentricity — that of the reclusive genius — is a central (and highly cultivated) part of Levin’s shtick. He really wants you to appreciate that he thinks differently — his own version of a diverse mind. Zarathustra coming down his mountain. Atlas shrugging. I fought the law and I won. You get the point. It’s very romantic. I have nothing against eccentricity, or mavericks, or romanticism. Quite the contrary, I’m into all three of these, big time! TAME’s revolutionary spirit in itself is not the problem. It is a novel perspective, no doubt. And it does manage to attract quite some interest from inside and outside science. Instead, the problem is that the revolutionary is not really with the rebellion. He is no underdog going against an evil empire. Instead, he is backed by powerful forces and shitloads of funding. He is the emperor! But an emperor that is wearing no clothes. There is no philosophical substance to TAME. None, whatsoever. There, I said it: TAME is an exemplar of whateverism. It means whatever you want it to mean. And that’s a feature of the whole thing, not a bug. I have principles, but if you don’t like them, I have others. Levin openly admits this himself: after presenting his fanciful panpsychist musings, he claims that you don’t actually have to buy into any of it to follow through on TAME’s empirical promise. The whole philosophy, apparently, is just decoration. Why present it at such length, you may wonder? I surely do. The reason, of course, is simple. The philosophy is there to feign sophistication, to look smart, and to attract other people who think of themselves as genius mavericks. It’s a public-relations gimmick. Levin’s preferred tactic is the motte-and-bailey: make some outrageous claims to get everybody’s attention and then, once you get a little pushback, immediately retreat to a more defensible position. Unfortunately, this kind of approach really isn’t very rigorous. Or serious, for that matter. And so the motte-and-bailey goes: “there are minds everywhere, from rock to biosphere.” However, you don’t really have to buy this. And also: “mind” doesn’t really mean what you think it does. The first bailey position simply isn’t true: you cannot buy into the research program envisioned by TAME without buying into its metaphysical baggage. It is not what it pretends to be: a down-to-earth, no-speculation, theory-light, empiricist approach, treating concepts such as “agency,” “intelligence,” and “mind” as indicative of uncontroversial and empirically observable phenomena. In reality, and I’ve said this already, TAME is loaded with metaphysical baggage that you simply cannot ignore. This is cleverly hidden by its intentional stance, which is a funny, almost ironic, kind of philosophy. Its purpose is to squeeze complex-sounding notions such as “selves,” “agency,” and “intelligence” into a simplistic Procrustean bed of mechanistic thinking. It aims to show that such concepts are not problematic, as long as we only use them as if they were real. A convenient shortcut to talk about teleonomy — apparent goal-directedness molded through evolution by natural selection. This allows Levin to talk about complex phenomena as if they were actually simple, easy to grasp, straightforward to engineer and control. In this sense, TAME is a framework explicitly designed for motte-and-bailey. It attracts an audience keen to move beyond reductionism in science, but sells them an empty package. There is no content, no substance, inside the shiny wrapper. Hence all the malleable and broad definitions. Take, for example, the term “intelligence.” What it boils down to is mere problem-solving, which is seen as a catch-all for “intelligent” goal-oriented behavior. An intelligent system is a system able to attain its goals in an efficient manner. That’s it. But where do these goals come from? And how are the problems to be solved identified and defined in any precise manner in the first place? TAME cannot answer these questions other than saying “teleonomy!” It must’ve evolved somehow. Pure hand-waving. And, of course, this is an extremely impoverished view of “intelligence.” An engineer’s view, not surprisingly. Upon closer scrutiny, you recognize pretty soon that it leads to an infinite regress: the definition of goals and problems is itself an optimization process which, in turn, needs to be optimized, and so on and so forth. It’s problems all the way down. Literally, in the case of TAME. True “intelligence,” as we use the term for ourselves and the behavior of other living creatures, includes things like being able to choose the right action in a given situation based on incomplete, ambiguous, and often misleading information. It means having common sense. It relies on the ability to be creative, to frame and reframe problems. It requires true agency: the ability to actually choose your own goals. The bottom line is: “agency,” “cognition,” and “intelligence,” as used by Levin, have nothing to do with agency, cognition, or intelligence as we would colloquially use these terms. They are lifeless computational caricatures. Zombie concepts. Devoid of any deeper meaning. And deceptive. Because the associations that naturally come with the everyday use of these terms are heavily used by Levin to push his agenda. He recently claimed that sorting algorithms can think. What this really means is the trivial statement that “sorting algorithms can solve problems.” Well, yeah. That’s what they have been designed to do. But it has nothing to do with human thinking or intelligence. Nothing at all. It's cones all the way down! A PROFOUND LACK OF ORGANIZATION Beneath all this superficiality lurks a deeper problem. Levin consistently ignores the one concept he’d actually need to build a reasonable philosophy of diverse minds. And this concept is the organization of living systems. In fact, TAME obliges him to ignore it, because of its dogma that you cannot draw any principled distinctions between living and nonliving systems. That’d be “Cartesian dualism” as Levin can’t stop pointing out. It just goes to show that he hasn’t really read his Descartes properly. Nor does he seem to understand the problem of life. Living systems behave in a qualitatively different manner compared to nonliving ones. Now that is an observable empirical fact. How else would it be so easy for us to distinguish a living organism from dead matter in our everyday lives? Life is what kicks back when you kick it. Even though a more precise definition of life is notoriously difficult to come by, we reliably manage to recognize life when we see it. Acknowledging this is not the same as embracing any kind of dualism. Quite the contrary: a true empiricist, you’d think, would want to come up with an explanation for this observed difference. In contrast, simply declaring that there is no difference goes very much counter our own experience. And it leads to all sorts of really counterintuitive claims about nonliving things having “agency,” “minds,” “intelligence,” and even “consciousness.” It doesn’t really mean anything. This, by the way, is my main issue with the ideology of panpsychism in general, not just TAME. It explains the origin and nature of agency and consciousness away, simply declaring them to be non-problems. If everything is conscious, what’s the big deal? But in this way, we’ll never learn anything about what these concepts actually mean, and how the phenomena they refer to came to exist in the world. This is where organization comes in: it gives us ways to productively think about these questions. But without it, this is hardly possible. Wait a minute, you may say: now you’re simply positing the opposite of TAME, that there is a fundamental difference between living and nonliving systems. But you don’t have any evidence for this either! Plus: organization adds additional conceptual ballast to your point of view. Is this really necessary? Gratuitously making up stuff is against empiricism! Whatever happened to Occam’s razor? The thing is, empiricism and theory are never far from each other: what you observe, and how you classify those observations, crucially depends on the kinds of questions you are asking. Those questions, in turn, depend on the concepts that you rely on to ask them. We have a chicken-and-egg situation here: we really cannot claim which came first — discerning observation or the theory that underpins it. In the best case, of course, the two co-evolve in a tightly coordinated manner. Therefore, it is completely legitimate to ask: what is it that makes living systems special? After all, we are able to robustly discern them from dead matter. And since life and non-life are made out of the same chemical ingredients, the answer must lie in how those ingredients interact with each other in living systems. The number one feat organisms achieve is that they manufacture themselves. And despite what Levin claims he can do with his “biobots,” or engineered hybrid or “autonomous” systems — no matter how much he attempts to mold the definition of a “machine” to his purposes — no machine humanity has ever constructed out of well-defined parts can manufacture itself. What’s worse: he mistakes self-manufacture for feedback-driven homeostasis. But the two are not the same thing. Feedback is a circular regulatory flow within some dynamic process, while self-manufacture describes the interaction between processes across scales that collectively co-construct each other. Even if we could build a self-manufacturing automaton (and, mind you, there is nothing that says we can’t), it would no longer be an automaton in the familiar sense of the term: a programmable mechanism with entirely deterministic behavior. Living systems are open-ended, constantly adapting to their surroundings in surprising ways, because they are self-manufacturing. Their behavior cannot be captured entirely by any formalized model. Their behavior is not completely predictable, and their evolution is beyond prestated law. Levin never ever touches on any of this. Why not? It’s weird. First of all, I’m sure he is aware of all the literature on biological organization that is out there (although he meticulously avoids engaging it in any serious manner). And, second, it is not normally like him to ignore any fancy idea that may appeal to his audience. So, what is going on here? The snag is exactly what I’ve just said, and it bears repeating: if you understand biological organization properly, you understand that it cannot be completely formalized. Living systems are truly and fundamentally unpredictable because of the peculiar way in which they are wired together. In this sense, they are very different from algorithmic processes, or any other rote problem-solving procedure. All of this goes fundamentally against Levin’s dogmatic (not empirical!) computationalism. Taking biological organization on board in any serious manner completely invalidates his whole approach. Poof! And it’s gone. The simple truth of the matter is: we cannot (and should not) think we can perfectly control and predict living organisms, or the ecological and social systems they are the components of. But this is Levin’s central aim, his dream, his claim to fame. He cannot let that go. TAME stands for “technology approach.” It’s about the domination of nature through engineering — not a deeper understanding, or respectful participation. Moving fast and breaking things, is what Levin is all about. Just look at the number of podcasts he appears on, the number of papers he publishes, the number of grants he obtains. It also explains the hype. Along his frenzied sprint into a techno-utopian future, he cannot possibly admit that nature is fundamentally not controllable, that there are limits to what we can and should do. That TAME is pure and utter hubris. So you see: it’s techno-utopian politics, not the search for truth and understanding, that drives this whole enterprise. TAME is not empiricism, but a cultish ideology with an agenda: to engineer everything, including the weather and humanity’s future evolution. But before we go there and have a closer look at that, let me briefly reexamine the claim that TAME will deliver biology from reductionism. That’s why his fans love Levine. But again, you will see that the good looks deceive: there is nothing to be found behind that pretty facade. ANTI-ANTIREDUCTIONISM So here’s the million-dollar question: is TAME really antireductionist? Well, I’d say it depends on what you mean by “reductionism.” I’ve already mentioned that Levin speaks out loudly and often against gene-centric approaches — the kind that only accept molecular genetic mechanisms as proper explanations in biology. Luckily such thinking is connected to a breed of biologists who are slowly but surely dying out. Yet, there’s still more than enough of these fossils around, so I will say this out loud: I support Levin fully when it comes to this part of his campaign! But then, to Levin, everything is bioelectricity. It is the general principle for all of biology, he claims. He talks about the “unifying rationality” of bioelectric fields, contrasting it with the “irrationality” of individual “cellular agents.” Smart tissues from dumb cells. Biobots, not moving blobs of tissue culture. And he not only claims to have evidence that bioelectric fields are in charge, that they allow you to “program the organism,” but also that they are conveniently modular, with distinct field states serving as “master inducers” of “self-limiting organogenesis.” Here we are: no more “one gene, one-enzyme” — but “one field, one organ.” I’ve heard this kind of thing before. A long, long time ago in a galaxy far, far away. I did my undergraduate diploma work in the lab of Drosophila geneticist and ultra-reductionist Walter Gehring at a time when dinosaurs still roamed the earth. And people in the lab back then were constantly talking about “master control genes” as “selectors” of “cell fate” and “master switches” in evolution. How naive of me to think this cartoonish view of development and evolution had died out! Because here it is: in Levin’s treatise on TAME, in the year 2022 CE. This time applied to fields, granted, not individual genes, but the principles and habits of thinking are the same: we are still looking for some localized central controller in biological systems in the hope we can find that knob to tweak. This is the direct opposite of antireductionism — anti-antireductionism. Or just plain reductionism, really. Yes, those fields are a property of a tissue, not a single gene or even an individual cell. But the approach is still reductive: it cuts all the complexity of biological systems down to a single explanation. Some kind of messiah y’all have chosen here: all of Levin’s talk about “agency,” “intelligence,” and “mind everywhere” is nothing but a smokescreen for just another kind of reductionism! What he presents is a mechanicist’s dream of predictability and control. Linear thinking at its most linear. Or, shall we say: a mechanicist’s illusion. The sorcerer's apprentice got lost in the woods ... THE SORCERER'S APPRENTICE

In the end: this has always been the point: if you don’t reduce nature’s complexity to simple principles, then you cannot dominate her. True complexity implies limits to control. But the techno-utopian cannot admit that. For we must take our destiny in our own hands. That’s the dogma. And to do this, we must fool ourselves into thinking we are the true masters of that destiny. At the same time, overly simplistic grand narratives of neverending progress no longer work these days. We are transiting rapidly from our modernist dream into a fractured postmodern post-fact nightmare. The zombie is the most accurate myth of our time. What does that tell us? And how many zombie movies do you know with a happy ending? The thing to do in such a world — if you are desperate to have an impact, to change the world in a way that really matters — is to sell yourself as some kind of metamodern messiah. Metamodernism is the new narrative. The next big thing to come. That which rebuilds after postmodernism’s deconstruction. And so you disguise your good old modernist tale in a fancy metamodern dress. The aim remains the same: to be fruitful and multiply, to subdue the earth. Engineer everything, yes! But don’t be too upfront about it. Instead, package your story in layers of glimmering obfuscation that cater specifically to metamodern hackers, hipsters, and hippies. TAME bristles with futurist engineering metaphors fertilized by the burning-man spirituality of “diverse intelligences and minds everywhere.” Levin sells himself as the metamodern visionary who can see further than the rest of us. He publishes papers about ethics, and produces AI-generated imitation indigenous poetry. What he’s telling you is that he cares. He will engineer everything responsibly — a weight upon his shoulders that few of us could bear. All he needs is your money and your attention! It’s bullshit at a very sophisticated level. And it’s dangerous bullshit at that. Don’t get me wrong: I do believe Levin is genuine about the whole thing. Unlike some other individuals I know, he seems too sanguine to be a real grifter or a fraud. He truly believes he is the chosen one — our Lisan al Gaib. But like Paul Atreides (or Brian), he is not the messiah. He is just a naughty boy. Because TAME is not good philosophy. And it is not a good foundation for any sustainable research program or policy either. The only thing that is fairly predictable in our complex world is that our attempts at engineering everything will have many unexpected (and unpleasant) side effects. Nothing ever goes as planned. The battle plan never survives the first battle. In the end, what survives is a bunch of more or less interesting empirical work. But, as I have argued, TAME cannot be judged by its empirical success alone. It is an integrated package. And some conceptual frameworks work better at generating hypotheses to be tested empirically than others. They may be broader, more productive, or more conducive to insight in some other way. One of Levin’s central claims is that TAME produces more and better experimental work quicker than any other conceptual frame. Yet, by refusing to engage with the peculiar nature of life — with its organization — Levin’s arguments fail to connect, and become intrinsically self-limiting. They aim high, yet fall short of their target. And they don’t even fail in any interesting way. Biobots are just moving blobs of cells, not “thinking machines.” Bioelectric fields remain to be explored, but will not be the promised cure-all. I could go on. By ignoring the special nature of living systems, TAME is actually narrower than any truly agential approach. In many ways, it goes in the right direction, yet still manages to miss the point. It restricts, rather than enables. It is a pair of conceptual blinders, not empiricism on steroids, as it would claim. Levin is the ultimate sorcerer’s apprentice. “Die ich rief, die Geister / Werd' ich nun nicht los.” The spirits he is summoning will be difficult to get rid of again. His vision is short-sighted, utterly modernist, not metamodern. There is not much new here. TAME is grandiose, but not grand. Its promise rings hollow. And its claims turn out to be rather vacuous after all is said and done. Nature is complex, mysterious, and beautiful. Sometimes, she is cold and cruel. It’s all part of the deal for a limited being in a large world. To find happiness is to fully participate in life. To go with the flow. Not to control, predict, and manipulate. Why obsess about engineering everything? It’s not going to happen, or not going to end well if it does. No amount of wishy-washy babble about intelligence and minds everywhere will convince me otherwise.

0 Comments

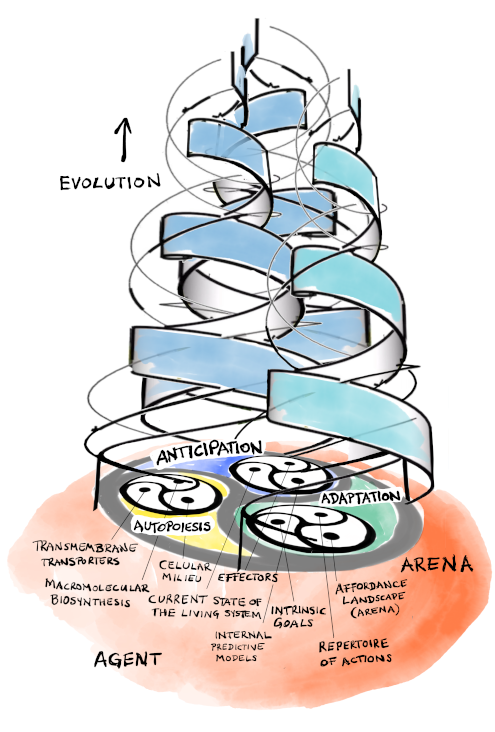

This blog post arose out of a conversation between myself, Eduard Willms, Tobias Luthe, and Daniel Christian Wahl, as part of the Designing Resilient Regenerative Systems teaching platform. Drawings by Marcus Neustetter. It accompanies a little video I made together with artist Marcus Neustetter, which explains the difference between living and non-living systems: 1. What are living systems, and how do they differ from non-living systems? Life emerges from the realm of the non-living as a new kind of organization of matter. Life is not distinguished by what it is made of, but by how it is put together, and how it behaves. Living systems are self-manufacturing physical systems. By “system,” we mean a bounded pattern in space and time, a patterned process, whose activity (as a whole) is in some way coherent and recognizable. Self-manufacturing systems exhibit autopoiesis, which is the ability to invest physical work to (re)generate and maintain themselves. To be autopoietic, a living system must not only constantly produce all its components, but it must also be able to assemble them in a way that ensures its own continued existence. This is called organizational closure. Living systems are bounded and limited beings: they are born and they die, and they are embedded in an environment that is much larger than themselves, an environment not (entirely) under their control. They adapt to this environment either short-term, by changing their physiology or behavior, or longer-term, through evolution. Because of their ability to self-manufacture and adapt to their environment, living systems have some degree of autonomy and self-determination. They do not merely react passively to the environment, but are anticipatory agents, initiating growth and/or behavior directed towards some goal from within their own organization. This applies to all life: from bacteria, to protists, fungi, plants, and animals (including humans). All living agents are also able to experience the world: all of them have some kind of sensorimotor capabilities, and an interiority (a basic kind of subjectivity, even if they do not have a nervous system to think with). They are therefore situated in an experienced environment, called the arena. This environment is full of meaning, full of obstacles and opportunities, full of encounters that are laden with value (either good or bad for you). This leads to an adapted agent-arena relationship: we are at home in our world ― embodied and embedded in our surroundings. In contrast, non-living systems (including human-built machines and computer algorithms) persist through passive stability (without effort), do not manufacture themselves, and do not have the capability to act, anticipate, or make sense of their environment. 2. What are the key features or characteristics that define a living system? Nonlinearity, feedback, being open and far from thermodynamic equilibrium, antifragility, self-organization, information-processing, hierarchical organization, and heterogeneity of parts and their interactions are all necessary but not sufficient to define a living system. There are many non-living systems that possess at least some of these attributes too. True hallmark criteria for life are: autopoiesis, embodiment, and existing in a large world. Not strictly required for life per se (but present in all life on earth) are the ability to evolve, heredity, and variation between individuals. 3. Examples of living systems at different scales:

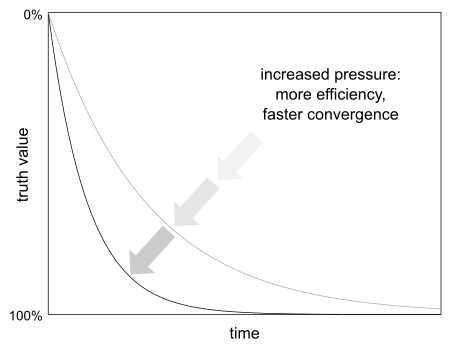

Things get more complicated when we think about multicellular life. Myxozoa, the smallest known animals, are about 20 µm across. In such creatures, the question arises: what is the autopoietic system here? The individual cell, or the whole body of the multicellular orga- nism? It can get complicated. Plants and animals, for example, differ greatly in how tightly they are organized at the higher level. Do we count the microflora in your gut as part of you, or not? Or think about cancer: it is a disease of cells becoming too autonomous for the good of the body they are part of. On the flipside, cells can commit “suicide” (apoptosis) during the development of a multicellular organism. It’s all a multilayered tangled mess!  Individual organisms can also form larger organizations, such as superorganisms (e.g. ant or termite colonies) or symbioses, such as lichens which are two species a fungus and an algae) peacefully living together, intimately sharing their self-manufacturing processes. This is called sympoiesis. Not everyone always fends for themselves in ecological communities! Quite the contrary. And the boundaries of living systems are fluid and ever-changing. Nothing ever remains still. The largest known organisms are not the blue whale, or the sequoia tree, but aspen groves (connected via their roots) and fungi called mycorrhiza, which can intertwine the cells and metabolisms of different host species across miles and miles of natural landscape forming a vast metabolic-ecological web of life! Why Study Living Systems? 4. How do living systems illustrate the concept of interconnectedness, and why is this crucial for our understanding of ecosystem health and the evolution of the biosphere? Interconnectedness is one of the basic principles of life. Transience is another. They both go together to form a multileveled dynamic web of connections between living processes. What results is an emergent and persistent higher-level order from constantly changing lower-level interactions. The singers change, but the song remains the same. It starts at the level of cells that talk to each other via chemical signals and extracellular vesicles called exosomes, or couple their cytoplasms together through gap junctions and other intercellular connections. At the level of tissues and organs, there are longer-distance means of communication and coordination, such as hormones transported through our vasculature or, of course, our nervous system. Organisms form a wide range of associations (see symbiosis above) and ecological communities. One of the most complex of these is the human eco-social-technological network of connections between us and a wide range of biospheric processes across many levels of organization. It is testament to how embedded we are in our environment. Such multilevel dynamic interconnections are essential for the persistence and resilience of biological organization, and its adaptation to changing circumstances. Individuals can only survive in a suitable context. Biological communication is therefore full of meaning: information is, according to Gregory Bateson, a difference that makes a difference. Life is where matter turns into mattering. Dynamic and adaptable interconnection increases coherence and robustness at all levels. Rigidity and disconnection is noxious to life. Living systems are anticipatory. Agents have internal models (forward projections) of what is likely to happen next in their arena. This enables them to choose actions with beneficial expected outcomes in many situations, to build strategies towards achieving their goals. Non-living systems are purely reactive, their behavior determined by their environment. Evolution, at the ecological level, can now be seen as a co-constructive dynamic between three processes (not unlike the triad underlying autopoiesis in the cell): (1) selecting goals to pursue, (2) picking appropriate actions from one’s repertoire, and (3) leveraging affordances (grasping opportunities or avoiding obstacles) in the arena. Life tends to create conditions conducive to life. This is the outcome of the intertwined processes of autopoiesis, anticipation, and adaptation. When this process is working as it should, we call it planetary salutogenesis. In the pathological case, where our behavior and disconnection undermine the stability of our ecosystem, we are harming ourselves. We become like cancer to ecological health. Our aim must be to attain the kind of freedom that a living agent can only get by working to preserve a coherent systemic context. 5. What can living systems teach us about resilience & adaptation in the face of environmental changes? Can non-human living systems transform deliberately, by intention? There are three distinct ways in which a system can react to perturbations (stress, shocks, noise, volatility, faults, attacks, or failures): it can be 1. fragile, unable to withstand even small perturbations, 2. robust, keeping its structure intact even under large perturbations, or 3. antifragile, improving its behavior under (certain kinds/amounts of) perturbation. The term resilience is used either for (2) or (3). We will stick to (3) below to avoid ambiguity. The kind of systems that humans have engineered so far are moderately robust (2) at best, but often they remain quite fragile (1). Think of the space shuttle, made out of 2.5 million moving parts, which was both the most sophisticated and one of the most dangerous means of transportation at the same time. Two out of six shuttles were lost: the Challenger in 1986, the Columbia in 2003. Space shuttles were complicated, yet fragile. Robust engineered systems also exist. Those rovers that survived the high-risk) landing on Mars all remained operational far beyond their planned expiration dates in an extremely remote and hostile environment. These machines were complicated and robust. What we can learn from living systems is that they are qualitatively different from both (1) and (2). They can not only resist perturbations but grab such challenges as opportunities to improve themselves. Living organisms are truly complex and antifragile (3) in a way our technological systems are not. This is Darwinian evolution in a nutshell: adaptation through natural selection in populations of individuals across many generations. But this is not the only way organisms can improve through challenges: they can also adapt their physiology, growth, or behavior to their arena (environment) as individuals within a single life span because they are autonomous agents. As the famous evolutionary biologist Richard Lewontin put it: “the organism is both the subject and the object of evolution.” This implies that organisms can and do transform themselves in ways which are both goal- oriented and adaptive (as described for question 4). We can call this deliberative change, but let’s be careful using the term “intention,” which is probably best reserved for organisms with complex nervous systems. Most creatures (e.g., bacteria or plants) act in goal-oriented ways without the ability to contemplate their actions. This distinction is important. Understanding the organization of living beings, which is both the precondition and outcome of evolution, is critical for us if we are to design and build antifragile self-improving systems. 6. What is the meaning of resilience and antifragility for the organism? 1. Self-manufacture must be resilient/antifragile for the living agent to persist. 2. Living agents which persist can come to know their world: they survive and thrive. 3. This leads to adaptation at the physiological, behavioral, and evolutionary scale. 4. Therefore, you need to be a resilient/antifragile agent to be evolvable. 5. The open-ended evolution of antifragile agents generates complexity and diversity. 7. Sustainability and regeneration: In what ways do living systems offer insights into sustainable living and regeneration? So far, we have neglected the relationship between agent and arena. Organisms never thrive in isolation. They are deeply embedded in populations, communities, ecosystems, and the biosphere. To come to know the world means to experience it first hand. Through embodied and embedded experience, the organism creates its own world of meaning ― from matter to mattering. There is coevolution of agent and arena. They mutually generate each other. Ecosystems arise through meaningful interactions between communities that consist of various kinds of agents and their respective arenas. These different arenas will not always overlap or harmonize necessarily. Sustainability implies coherent dynamics and adaptation across many levels of organization. Out of an ever-changing tangle of synergies and ten- sions, cooperation and conflict, higher-level order can arise. In the case of parasitism (the virus), symbiosis (the lichen), and the superorganism (the ant), such multilevel coherence is an urgent necessity, an essential part of the self-manufacture of the organism itself. Less tight interweavings are also possible. In fact, most communities and ecosystems show some antifragility, but are not straightforwardly self-manufacturing above the individual level. They lack the closure of an organism, being more open and fluid, their components more exchangeable and less intimately interlinked than those of the individual agent. The typical dynamic organization of such a multilevel system is that of the panarchy (or holarchy): a nested, dynamic, interlocked hierarchy of adaptive cycles that occur across multiple spatial and temporal scales. Each of these cycles consist of four phases: 1. growth, 2. persistence, 3. release, and 4. reorganization. They can occur at many levels, from the life cycle of an individual organism, to the dynamics of an entire bioregion. Cycles at higher levels of organization tend to proceed more slowly than those at lower levels. This gives the multilevel system its resilience. Rapid low-level turnover enables innovation for adaptation (flexibility), while longer-term dynamics at the higher levels provide the capacity for innovations to accumulate (stability) before more global change occurs. Thus, in fact: the singers change but the song remains recognizable while slowly changing. Sustainable living and regeneration can only be understood in this wider context. Not only is the persistence of an individual rooted in its own constant regeneration, but the entire eco- system depends on the antifragile absorption and adaptation that results from the constant and rapid turnover of its components. Life is never standing still: like the Red Queen in Lewis Carroll’s “Through the Looking Glass” it must always run to stay the same. This is why the often-used term “homeostasis” can be misleading. It gives us the impression of a balanced stasis (a quiescent equilibrium) in nature, reaching some point of perfection that we must also strive to attain. Yet, such perfection means nothing but death to living systems. The natural world is messy, constantly changing, constantly cycling between birth, growth, and decay. Biological stability must be seen as repetitive and regenerative instability. To persist we must change. Regeneration means to act towards sustainability. Deliberative coevolution: to actively participate in our world with all the foresight and care we can muster. Living Systems and Societal Challenges 8. How can principles learned from living systems inform our approach to solving contemporary societal crises, such as climate change, biodiversity loss, and lack of sustainability? Two aspects are central to our move from dominion to stewardship: 1. We must pay close attention to the rates of change in our social-ecological system. 2. We must shift our paradigm from control/prediction to participation. One of the major lessons we learn from the unique complexity of life is the following: the only thing we can always expect when manipulating the living world is that there will be unexpected consequences. By definition, those consequences are rarely aligned with the initial goal of our intervention. Climate change, biodiversity loss, and our current lack of sustainability are all consequences of this kind. Nobody really intended them to happen. One of our reflexes in this situation may be to focus on conservation. In times of widespread breakdown and decay, it is natural to want to suppress change. But this misunderstands the panarchic nature of natural multilevel systems ― their constant adaptive cycles of birth, growth, death, and regeneration. Robustness through stasis is not an adequate solution. The trick is not to avoid or attempt to control change, but to fully appreciate the quality and rate of the change that is always happening. Our ability to predict and control is limited. This recognition is fundamental. Instead, we must go with the flow. We must engage in serious play with ideas whose consequences cannot be foreseen. We must foster diversity and innovation of a kind (and at a rate) that does not overwhelm the higher-level stability of our social-ecological system. We must heed both the flexibility and the stability of the panarchy. Sustainable participatory change means slowing down, cautiously moving forward while constantly monitoring outcomes and adapting to the unexpected. Sustainable participatory change also means fostering the right kind of diversity to increase adaptive capacity. In an unpredictable environment, a large repertoire of strategies is key. As Fritjof Capra says: a machine can be controlled, a living system can only be disturbed. At best, we will find ways of carefully nudging a living system. According to Donella Meadows, we must find its leverage points, those pivots that allow us to influence system behavior. Most importantly: after each cautious inter- vention, we must patiently observe and listen. To achieve this, design must move away from optimization, which is the enemy of diversity and the hallmark of machine thinking. To aim for optimization means to treat the world as a mechanism. It leads us into a vicious race to the bottom, a headless competitive rush, with our eyes wide shut, into an uncertain future. We are accelerating towards the abyss. We urgently need to move away from this kind of thinking. Regenerative systems design requires us to trade off optimality and speed for resilience. We have to finally learn that you cannot have your cake and eat it. 9. Lessons for human societies: what lessons or strategies from living systems could be particularly useful for designing resilient and adaptable human societies? An excellent example of how machine thinking impedes progress concerns the way we currently organize and fund basic scientific research. The key idea is to increase the productivity of discovery by putting increased pressure on individual scientists to publish and to obtain funding from competitive sources. This idea fundamentally misunderstands the creative nature of the process of scientific investigation. First of all, it is important to realize and remember that the societal function of basic research is not primarily to produce technological innovation, or to solve practical problems. Instead, basic science is useful to a resilient and adaptable human society because it provides deeper and broader insight into the world we live in: it allows us to better understand what is going on around us, and to explain these goings-on in a way that is robust and relevant to the problems our society is facing. This is fundamental to our ability to choose the right action in a given situation. We must aim for wisdom, not just knowledge. Yet, modern science is not organized in a way conducive to these aims. Instead, it strives for control and prediction, rather than understanding. It maximizes output, quantity over quality, rather than rendering the process of investigation resilient and reproducible. It emphasizes competition, when cooperation and openness are needed because there is so much more to discover than all scientists on this planet together could ever hope to cope with. It fosters an intellectual monoculture, when diversified perspectives are needed for innovation and adaptation to unexpected situations. It promotes risk-averse opportunists and careerists, when we should encourage explorers who dare to take on the monumental challenges of our time. In summary: the way we organize science these days is tuned towards short-sighted optimization and efficiency, rather than a sustainable and participatory way forward. In evolution, when too much selective pressure is applied to a population, the process of adaptation gets stuck on a local maximum of fitness, unable to explore and discover better solutions nearby. Diversity is reduced, deviation is harshly punished. This is exactly what happens in basic research today: too much pressure impedes the adaptive evolution of scientific knowledge, preventing it from effectively exploring its space of possibilities for better solutions. The machine view and its focus on optimization kills sustainable progress for all by sacrificing it for a fragmented measure of short-term productivity. This is why we need a new ecological vision for science. Once again, slowing down and fostering diversity are central to this much needed scientific reform. Time scales and societal levels are of fundamental importance for our assessment of progress: our exclusive focus on individual short-term productivity fosters self-promotion, hype, and fraudulence, which violently conflict with resilient progress of the whole scientific community towards sustainable growth, deeper understanding, and collective wisdom. Similar shifts from optimization to resilience are due in our education and health systems. In all these areas, our focus must lie on nurturing creative innovation, rather than squeezing human activities into the Procrustean bed of short-term efficiency and accountability. Analogies and Applications 10. Are there analogies from living systems that you find especially powerful or illustrative for understanding human-made systems or societal structures? Sustainable regenerative design must not only look to specific natural materials (adhesive pads) or patterns (camouflage) for inspiration, but to more general dynamic principles and relationships between parts and whole which differ from those currently used in machine design.We have already discussed that regenerative systems and societies will be less optimized and controllable than machine-inspired ones. In turn, they will be more diverse and bent towards adaptive exploration. And they will progress in an integrated way at the pertinent spatial and temporal scales. Too slow, or too fast, and you cannot adapt and survive. Coordinated timing and multiscale coherence are everything in regenerative design! A good analogy to highlight this is the machine workshop vs your garden. Machines need constant external maintenance because they fail to be self-manufacturing or sustainable. Living agents, and the higher-level agential systems that contain them as components, do best when maintaining themselves. When nurturing your garden, you only provide the right circumstances that allow the organisms in it to flourish together. The exact same applies to regenerative systems of all kinds: they must be given the freedom and the conditions to flourish by themselves. This means both stewardship and a certain hands-off attitude. As the Daoists teach us: it is important to consider that no action is often the best way forward. Apart from engineering vs. nurture, we need better analogies that ground our higher-level self-organizing systems in the physical world again. Societies and economies, for example, should be seen as forms of energy metabolism: recent human history has occurred in the context of the energy abundance caused by the carbon pulse. As we have exploited and depleted our easily accessible free-energy sources on the planet during the past 400 years, our society has become energy blind. We are taking energy abundance for granted. One peculiar aspect of this energy blindness is the idea of a circular economy. At first sight, this seems like a reasonable analogy to the organizational closure of a self-manufacturing organism. But it is not. We have seen above that stability at the ecosystem level is not due to closure, but rather to its panarchic dynamic structure of nested adaptive cycles. This is why we should be skeptical of the metaphor of society as a “superorganism”). Note that organisms exhibit closure only in the sense that they produce and assemble all the components that are required for their further existence. In contrast, like any other physical system that exists far from equilibrium, they are thermodynamically open to flows of matter and energy. By analogy, an economy that is closed to such flows is therefore an impossibility. At best, our economies can strive to achieve what organisms do best: to recycle and reinvest the waste that accumulates and the heat that is dissipated during the construction of their own organization. While a hurricane burns through its source of free energy at maximum rate, leaving a path of destruction in its wake, human societies should seek to imitate organisms instead, which also burn free energy at maximum rate but reinvest the output of this process into their own self-maintenance. This is the true meaning of circular here. 11. Could you highlight innovations or technologies that have been inspired by living systems? The surprising (and disappointing) fact is that there are very few innovations and technolo- gies that are widely distributed and take the principles underlying living systems to heart. Instead of providing a list of examples, we will therefore consider two alternative ways forward from here. The first is prevalent in traditional complexity science and contemporary biology. There are many researchers whose work on the fundamental principles of living systems still aims to increase our ability to predict and control them for our own purposes. A concrete example are xenobots, mobile clumps of cultured cells extracted from the clawed frog Xenopus laevis. These clumps can be shaped and move in ways that are somewhat predictable by AI algorithms. After a certain amount of growth, they also fall apart and reassemble in a way that roughly resembles reproduction. This has led to claims that we can build useful machines (“bots”) from such cellular systems that have truly agential properties. Others have proposed to engineer systems with artificial autopoiesis, an idea which goes back to 1966 when polymath John von Neumann presented his concept of a universal constructor: a machine that can self-manufacture. So far, these studies remain at the level of computer simulations. This kind of research faces a number of very daunting challenges. (1) We do not have the kind of mathematics that would be required to predict and control such systems. (2) We lack a suitable architecture design for such systems. (3) We do not seem to be able to construct the kind of materials that would allow us to actually build them. Thus, this kind of technology, if possible at all, seems very far off at the moment. A more important question concerns the desirability of such autopoietic agentic constructs. By definition, they would be able to set their own goals and pursue them. This means that we would face a considerable problem of alignment: they will not necessarily do what is in our interest. In addition, we’d face a moral conundrum: would it be ethical to force them to do our bidding? After all, that is not what they want. Agential technology would be a mess. That is why we believe there is a better way forward: the construction and evolution of sustainable regenerative systems that include technology and living agents co-existing in a harmonious and coherent whole. The idea here is not to control and predict, but to evolve and progress together, in a way that not only acknowledges but cherishes and harvests the fundamentally unpredictable but adaptable nature of living systems. This is technology design and development that knows its own limitations, that considers machines and their effects in their embedded natural context. It is participatory design. We have yet to truly see it in the modern Western world. The time for it to (re)emerge is now. Future Directions 12. What are the most promising areas of research or innovation where living systems principles could have a significant impact? Most importantly, we need regenerative design for the great simplification, our coming transition from an age of unbounded exploitation and energy abundance to what hopefully will be an age of resilient sustainability. Living systems principles are needed for us to be good stewards of our social-ecological systems. And we need these principles too for designing the education, research, and health systems of the future. We need them for technological innovation, to generate low-tech solutions to humanity's most essential needs ― especially those that currently depend on abundantly available fossil energy. In short, we need regenerative design for literally everything and everyone right now: we need a completely different business model for sustainable innovation! Regenerative design is not about improving this or that particular technological artifact. It is about redesigning the whole context and the processes through which we generate solutions to our problems. We urgently need to change our philosophy from “move fast and break things” to first ask ourselves: why am I doing this? And: who will benefit? If you do not have very clear answers to both of these questions, don’t do it! Stop racing mindlessly into the unknown. While this mindless and broken race continues, before it hits the inevitable wall of physical limits on a finite planet, we must use living systems principles to make regenerative systems design itself a self-maintaining pattern! This requires building societal niches ― communities and eco-social environments ― in which regenerative design practice thrives and diversifies. Once the metacrisis has finally caught up with everyone, we need to be ready with an arsenal of possible practices and solutions. It is not regenerative design, if it is not resilient itself. 13. How can we incorporate living systems thinking into education and public awareness to foster a more holistic understanding of our relationship with the natural world? The machine view of the world is inoculated into young minds at an early stage, starting (in earnest) during early adolescence, the most transformative phase in a human being’s life. Kids know instinctively that the world is beyond their grasp. There is little they understand, and every day of their lives is full of surprises and unexpected learning opportunities. During adolescence, humans transform from light-hearted players in an infinite game, where the aim is not to win but to bend and change the rules, to serious masters of our own fate. This is the time in our life when we need to hear about living systems principles most, when we need to learn how to become good participants in the infinite game of life. Each child should be allowed to choose their own path through this transformative learning experience. We cannot just talk about living systems principles, we must actively explore and experience the flow of energy through every natural system. We must become part of this flow. Only by instilling this kind of wisdom can we overcome our energy-blindness to inspire and enable ecological agency. This is one of the most crucial endeavors for our time. We can no longer wait with its widespread implementation. 14. What challenges do we face in applying living systems principles more broadly, and what opportunities do you see for the future? We are stuck in a game-theoretic trap ― a global race to the bottom. Our societies are driven by the irrational dogma that unbridled competition leads to continued progress. The grip of this dogma on us is pretty comprehensive: it is visible at all levels, from our hyper- individualism and personal disconnection to our nations being locked into an deluded spiral of accelerating growth. This kind of rivalrous dynamic inevitably results in a self-terminating civilization, with exponential technological innovation opening a catastrophic gap between itself and our limited ability for inner growth and societal maturation. It is extremely challenging to implement sustainable regenerative solutions in such a chaotic and ever-accelerating dynamic environment. How can we slow down without being immediately left in the dust of unstoppable progress? How can we foster diversity in a system based on relentless and single-minded optimization? How can we be heard over the deafening din of a cultish and toxic technological utopianism? How do we move beyond the self-reinforcing politics of deliberate denial? Is it possible to throw ourselves in front of this 1000-ton bolide heading for a cliff without getting run over and mauled to death? Buckminster Fuller famously stated: “[y]ou never change something by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete.” We’d better heed his timeless advice. The existing model is on an exponential trajectory of making itself obsolete. Collapse at a massive, probably global, scale is bound to happen in the very near future. The secret is to be ready with workable solutions once the world comes crumbling down. The challenge we face is to build the required societal niches in which to develop and sustain a diversity of such solutions. They won’t be very competitive in the current system, but they’ll outlive it for sure. To quote what is perhaps an unlikely source in this context, the economist Milton Friedman: “Only a crisis ― actual or perceived ― produces real change. When that crisis occurs, the actions that are taken depend on the ideas that are lying around. That, I believe, is our basic function: to develop alternatives to existing policies, to keep them alive and available until the politically impossible becomes the politically inevitable.” If we learn one thing from neoliberalism, the ideology that got us into this mess in the first place, it should be this: be ready when it’s your time to change the world! 15. What is the role of living systems labs, places and spaces with open system boundaries to experiment with enacting social-ecological systems and their emergence? These are the niches that provide a home for experiments with a diverse range of proposed regenerative systems designs. In an unpredictable world, such diversity is a necessity. And we need to get out of the classroom while teaching! Workable solutions require embodied and embedded practice. Part of this practice is to make people comfortable with the uncertainty inherent in the process. We must play! But this is serious play. Infinite play. We don’t aim to win. Instead, we aim to change the rules so we can continue playing. Final Thoughts 16. What advice would we give to practitioners, policymakers, or the general public interested in applying living systems principles to address environmental and societal challenges? Sustainable practice includes the practitioner: pace yourself accordingly. Process thinking includes the thinker: anchor yourself in the moment and go with the flow. Embedded practice includes the practitioners: work on your network of relations. Seek out like-minded people. This is not something you can do alone. Expect the unexpected. Nobody knows where all of this is headed. Be ready to release your own preconceived notions. Long-term planning is overrated (and impossible in these times). Ask yourself not: where am I going? But: am I going someplace? Make sure you're properly adapting to circumstances as you go along. Don’t lose your grip on reality. And never forget: things will get better after they get worse. This has all been said a thousand times before… still, it’s surprisingly hard to really live it. 17. How do you envision the role of living systems thinking evolving in the next decade, particularly in relation to global sustainability efforts? It’ll be huge, simply because it is the only approach that will actually work in this world of ever-increasing complexity. But we’ll also see a lot of reactionary backlash in the next few decades, people deliberately ignoring the actual world as long as they can, trying to escape into a simpler, more controllable, machine reality. Brace yourself. None of this will work. The world is what it is, and it is not getting any simpler. Don’t waste too much time trying to convince people with words. Show them that you have better solutions. Regenerative solutions for a more sustainable world.